Clinical Research & Data, IABP, AMI Cardiogenic Shock, Right Heart Failure

Intra-aortic Balloon Pump (IABP) FAQs

1. How does IABP work?

Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) counterpulsation—synchronized inflation during diastole and deflation during systole—aims to reduce myocardial oxygen demand and increase myocardial oxygen supply. The vacuum created by deflation immediately prior to systole helps reduce afterload and improve forward flow from the left ventricle.13,14 There must, however, be native left ventricular function for optimal benefit with IABP support.1

While balloon counterpulsation augments aortic pressure (AoP), this increase may not improve cardiac output or decrease pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP). As shown in a HARVI hemodynamic simulation (harvi.online), activating IABP only increased cardiac output 0.4 L/min with minimal reduction in PCWP.

2. Is there a role for IABP in cardiogenic shock?

IABP-SHOCK II and IABP-SHOCK II Follow-up Data Demonstrate No Survival Benefit to IABP in AMI Cardiogenic Shock

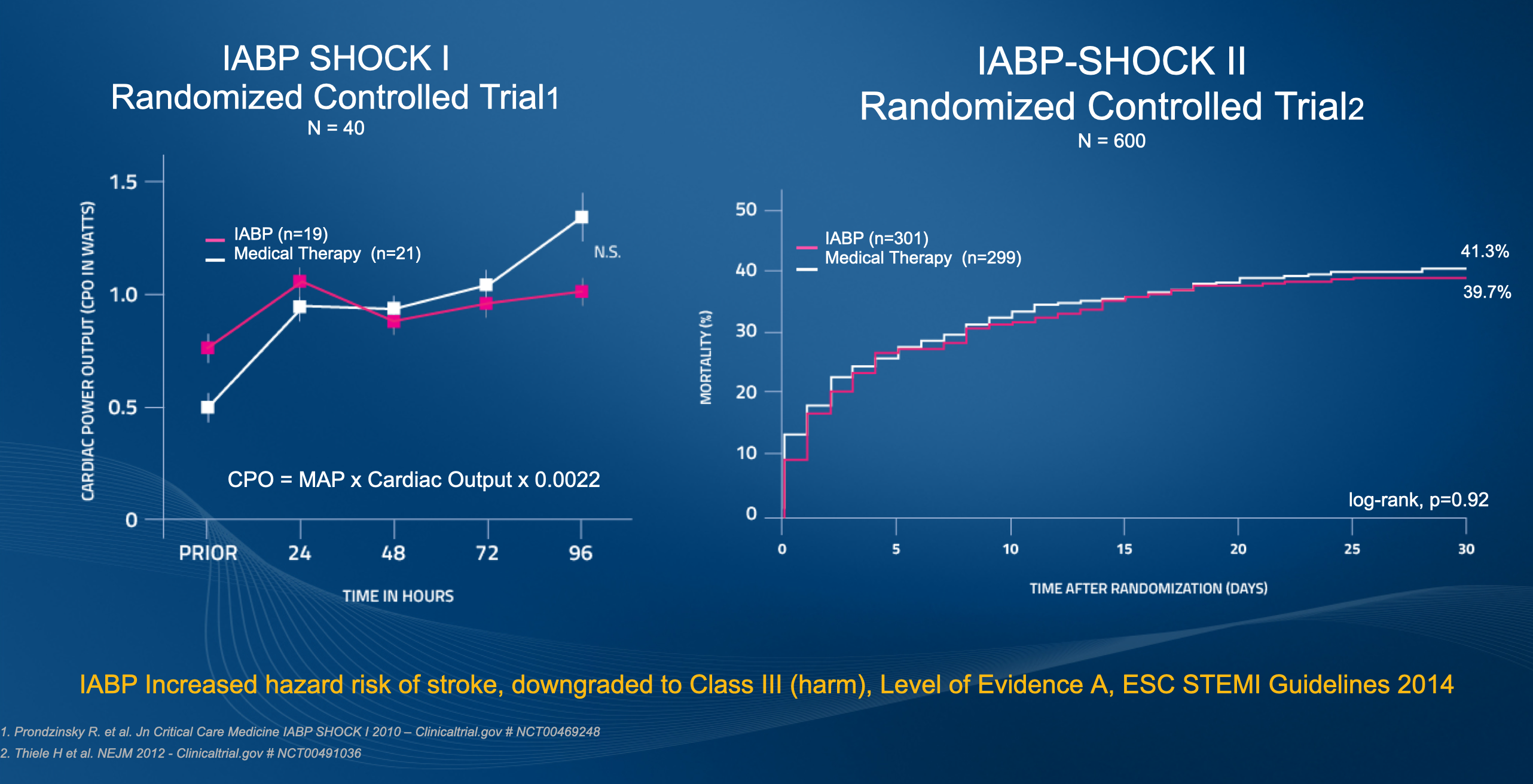

Initial IABP SHOCK II results

Results from the Intra-aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock II (IABP-SHOCK II) trial published in 2012 demonstrated that use of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation did not significantly reduce 30-day mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction (AMI) for whom an early revascularization strategy was planned.2

In this randomized, prospective, open-label, multicenter trial, 600 patients with cardiogenic shock complicating AMI were randomized to receive IABP (pre-PCI or post-PCI per operator discretion) or no IABP. The treatment plan was for all patients to receive the best available medical treatment according to guidelines and undergo early revascularization. Nearly all (95.8%) patients underwent primary PCI with 3.5% undergoing immediate coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) or initial PCI with subsequent CABG and 3.2% of patients receiving no revascularization.2

In addition to no difference between groups in the primary endpoint of 30-day all-cause mortality, there was no difference in mortality between patients receiving IABP pre-PCI (13.4% of patients in the IABP group) and patients in whom the balloon pump was inserted after revascularization (86.6% of patients in the IABP group).2 There were also no differences between treatment groups in the secondary outcomes of bleeding, ischemic complications, stroke, time to hemodynamic stabilization, ICU length of stay, dose and duration of catecholamine therapy, and renal function. The study also revealed no immediate improvement in blood pressure or heart rate between treatment groups, nor did IABP significantly affect levels of C-reactive protein or serum lactate, both measures of inflammation and tissue oxygenation.2

Long-term 6-year IABP SHOCK II outcomes

Long-term 6-year outcomes of the IABP-SHOCK II trial also demonstrate that IABP has no long-term effects on all-cause mortality. Follow-up was completed for 98.5% of the 600 patients initially enrolled in the trial. In addition to no difference in mortality, there were no differences in recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke, repeat revascularization, or rehospitalization for cardiac reasons. NYHA class and EuroQol 5D questionnaire measures also revealed no differences in survivor’s quality of life.3

3. What do clinical guidelines say about the use of IABP in cardiogenic shock?

Routine placement of IABP in the setting of cardiogenic shock is a Class III (level of evidence B) recommendation in the 2017 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the management of AMI in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation.4 The Class III definition reads: “Evidence or general agreement that the given treatment or procedure is not useful/effective, and in some cases may be harmful” or, more colloquially, “Is not recommended.”

The 2017 ESC guidelines cite data from IABP SHOCK-II for this recommendation. Data from the 6-year long-term follow-up from IABP-SHOCK II further supports this recommendation. As noted in a 2019 editorial regarding the follow-up data, Judith Hochman, MD, and colleagues write, “Thus, the IABP-SHOCK II follow-up data provide additional evidence to support a limited role for IABP in acute MI with cardiogenic shock in the modern era.” This editorial also states, “The next iteration of North American cardiogenic shock guidelines should also be updated to reflect these randomized clinical trial data and put an end to the clinical inertia that has perpetuated routine use of IABP for cardiogenic shock.” 1

Another source referenced in the 2017 ESC guidelines is the Counterpulsation to Reduce Infarct Size Pre-PCI-Acute Myocardial Infarction (CRISP AMI) trial, which showed no reduction in infarct size between the IABP plus primary PCI group compared with PCI alone group among patients with acute anterior STEMI without cardiogenic shock. 4,5

4. Is there a role for IABP in Protected PCI?

BCIS-1 study

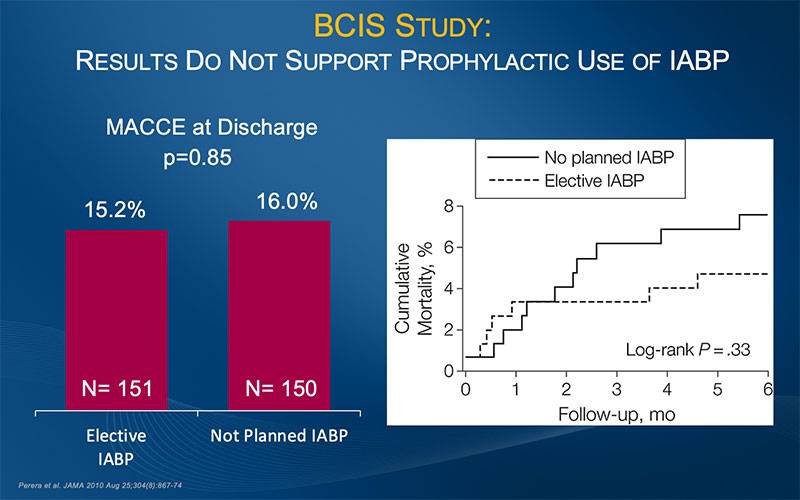

BCIS-1 Results Do Not Support Prophylactic Use of IABP for PCI

Results from BCIS-1 (Balloon Pump-Assisted Coronary Intervention Study) demonstrated that elective IABP insertion did not reduce the incidence of major adverse cardiac and cardiovascular events (MACCE) following PCI. The authors concluded that these results do not support a strategy of routine elective IABP insertion before high-risk PCI.6

BCIS-1, the first randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of elective IABP use in patients undergoing high-risk PCI, was a prospective, open, multicenter, randomized controlled trial conducted in 17 tertiary referral cardiac centers in the UK between December 2005 and January 2009. The study randomized 301 patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction and extensive coronary disease to undergo elective IABP insertion before PCI or to undergo PCI without planned IABP support. The trial sought to determine whether routine IABP before PCI reduces MACCE in patients with severe LV dysfunction and extensive coronary disease. MACCE was defined as death, AMI, cerebrovascular event, or further revascularization by PCI or CABG surgery at hospital discharge (capped at 28 days). Secondary endpoints included all-cause mortality at 6 months, major procedural complications (including prolonged hypotension, ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation requiring defibrillation, or cardiorespiratory arrest requiring assisted ventilation), bleeding, and access-site complications.6

In addition to demonstrating no difference in MACCE at hospital discharge, the study results showed that elective IABP use, while associated with significantly fewer procedural complications, was also associated with more minor bleeding and more access-site complications than PCI performed without planned use of IABP. The authors write, “These results do not support a strategy of prophylactic placement of an intra-aortic balloon catheter during PCI in all patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction and a high myocardial Jeopardy Score.” 6

PROTECT II Randomized Controlled Trial

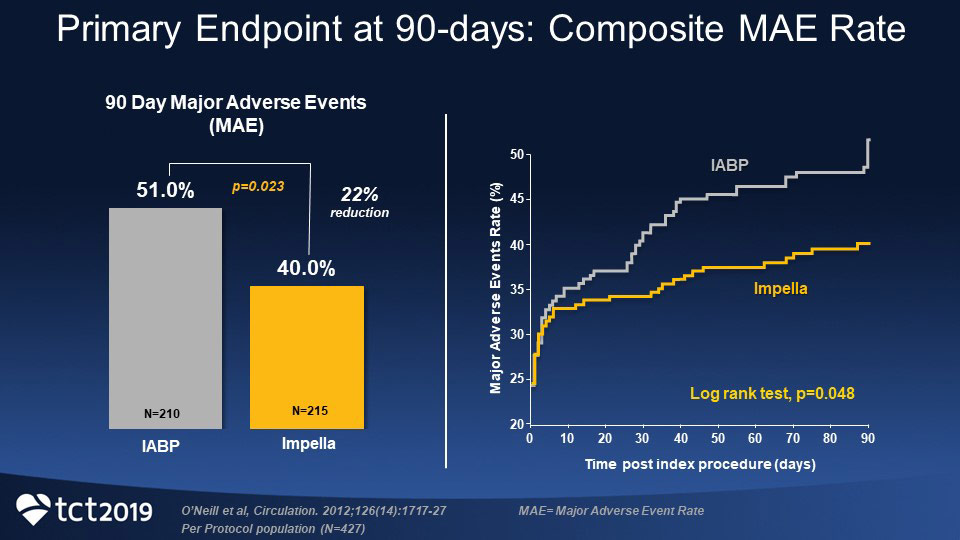

Significantly Lower 90-day MAE rate in Impella 2.5® Arm Compared to IABP Arm in PROTECT II RCT

Results from the PROTECT II randomized controlled trial demonstrated significantly lower 90-day major adverse event (MAE) rate in the Impella 2.5® arm of the trial compared with the IABP arm (40.0% versus 51.0%, P=0.023), yielding a relative risk reduction of 22%.7

In addition, in the high-risk population that underwent PCI, use of Impella heart pumps compared with IABP resulted in a 29% reduction in MACCE at 90 days—22% in the Impella group compared with 31% in the IABP group (p=0.034).8 Most events happened after hospital discharge.8

PROTECT II was a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) in patients undergoing nonemergent high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The study was designed to assess whether an Impella-supported high-risk percutaneous revascularization strategy would result in better outcomes than a revascularization strategy with IABP support.1

5. What do key opinion leaders have to say about IABP use?

KOL: Jacob Møller MD, PhD

Jacob Møller MD, PhD, who recently published a paper on contemporary trends in the use of MCS in patients with AMI cardiogenic shock, 9 explains that in Denmark after publication of the IABP-SHOCK II results in 2012, “more or less overnight… we stopped using the balloon pump for the indication of shock and AMI.” Dr. Møller is an intensivist at Copenhagen University Hospital.

KOL: Giuseppe Tarantini, MD, PhD, FESC

Describing data from several IABP studies, Giuseppe Tarantini, MD, PhD, FESC, notes, “We did not observe any benefits with intra-aortic balloon pump and unloading with balloon pump even though you go pre-PCI.” Highlighting IABP data from various types of patients from BCIS-1 RCT,6 CRISP-AMI,5 cVAD Study,10 IABP-SHOCK II,11 and a meta-analysis in ECMO patients,12 Dr. Tarantini explains, “you won’t see any significant advantage in terms of MACCE, infarct size, survival, and so on.” Dr. Tarantini is professor and director of interventional cardiology at the University of Padua in Italy and president of the Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology-GISE.

References

- Katz, S.D., et al. (2019). Circulation, 139, 404-406.

- Thiele, H., et al. (2012). N Engl J Med, 367(14), 1287-1296.

- Thiele, H., et al. (2018). Circulation, 139(3), 395-403.

- Ibanez, B., et al. (2018). Eur Heart J, 39(2), 119-177.

- Patel, M.R., et al. (2011). JAMA, 306(12), 1329-1337.

- Perera, D., et al. (2010). JAMA, 304(8), 867-874.

- O’Neill, W.W., et al. (2012). Circulation, 126, 1717-1727.

- Dangas, G.D., et al. (2014). Am J Cardiol, 113, 222-228.

- Helgestad, O.K.L., et al. (2020). Open Heart, 7:e001214.

- O’Neill, W.W., et al. (2014). J Interv Cardiol, 27(1), 1-11.

- Fuernau, G., et al. (2020). Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. doi: 10.1177/2048872620930509.

- Cheng, R., (2015). J Invasive Cardiol, 27(10), 453-458.

- Weber, D.M., et al. (2009). Cardiac Inter Today Supp, Aug/Sep, 3-16.

- Burkhoff, D., et al. (2015). J Am Coll Cardiol, 66(23), 2663-2674.

NPS-1846